Learn

Introduction

ESG reporting seeks to create a standard way for a range of investors to understand a company’s (or a fund’s or an asset’s) financial and non-financial impacts, as well as the strategy, approach, and performance of the company as it seeks to make those impacts. In this series of articles we are exploring how bioeconomy companies can tap into opportunities created by the growth of ESG investing, and more broadly how ESG reporting can help bioeconomy companies improve and de-risk their operations.

ESG investing has evolved organically and competitively over the last few years. In truth, the rapid increase in ESG participants, standards, frameworks, and nomenclature has created a jumbled and confusing

landscape. Numerous stakeholders and service providers are creating an ESG ecosystem that consists of:

- Reporting Frameworks

- Databases

- Data Aggregators

- Corporate Rating Agencies

- Fund Rating Agencies

- External Assurance Providers (i.e. Auditors)

Unpacking ESG Reporting

ESG reporting has grown confusing. According to Mike Wallace, formerly of the Global Reporting Initiative, “It is a confusing space for new entrants when one considers the various options, requests and suggestions for how to address the growing demand for ESG information [with] at least a half-dozen disclosure options.” ESG reporting has become a catch-all term for communicating quantitative and qualitative corporate impacts, even though there are several distinct audiences for this information. Stakeholders as varied as customers, employees, industry peers, environmental NGOs, investors, and ESG ratings agencies will be interested in a company’s disclosures, but they are interested for different reasons. The key to disaggregating these audiences is financial materiality.

Many stakeholders will be interested in a company’s behavior and ESG impacts. These stakeholders might be issue driven. Is a company effectively combatting climate change? Is it reducing de-forestation?

Is it compensating workers ethically? ESG reporting can inform these customers, peers, community members, and issue-driven investors.

ESG reporting can also be considered quantitative branding. From that perspective, ESG reporting is a type of sustainability branding and marketing. Although branding and stakeholder engagement are significant corporate activities and certainly can impact a company’s value, these are not the investor stakeholders of primary concern to us in these articles. We believe that bioeconomy companies should provide 1) ESG reporting and for investors that are examining a company’s financially material “management discussions and analysis” (MD&A) and 2) ongoing reporting for investors and the public.

Financially Material ESG Reporting

We are interested in helping bioeconomy companies understand ESG reporting so as to drive three positive financial outcomes:

- Recruit diverse ESG and/or impact investors.

- Support investor relations over time by providing financially material ESG data.

- Improve and de-risk operations by aggregating and analyzing one’s own ESG data.

Given the (many) existing requirements that biofuels and bio-based products have in order to be certified sustainable, bioeconomy companies may be surprised to hear that they need to learn another reporting language. There is certainly considerable overlap between the data requirements for sustainability certification and ESG reporting, particularly for metrics of climate and (E)nvironmental impact. However, bioeconomy companies can benefit from expanding their reporting beyond environmental sustainability (e.g. water quality and use, air quality, and carbon scoring) to include their (S)ocial impacts and approaches to (G)overnance.

Two of the leading reporting frameworks are the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) and the Sustainable Accounting Standards Board (SASB). Their different approaches highlight the split between reporting to a general sustainability audience versus an MD&A audience.

The Sustainable Accounting Standards Board seeks to be for sustainability what that Financial Accounting Standards Board is for financial reporting. Like FASB (and GRI), SASB is a non-profit that develops standards with considerable stakeholder input. Unlike GRI, SASB is most interested in financially material sustainability disclosure. SASB (and others) recognize that there are many challenges to ESG reporting. How does one compare businesses across sectors? How does one compare start-ups versus more established firms? How does one discriminate which aspects of sustainability are financially material? How does one accommodate industries, like the energy sector, that are in transition?

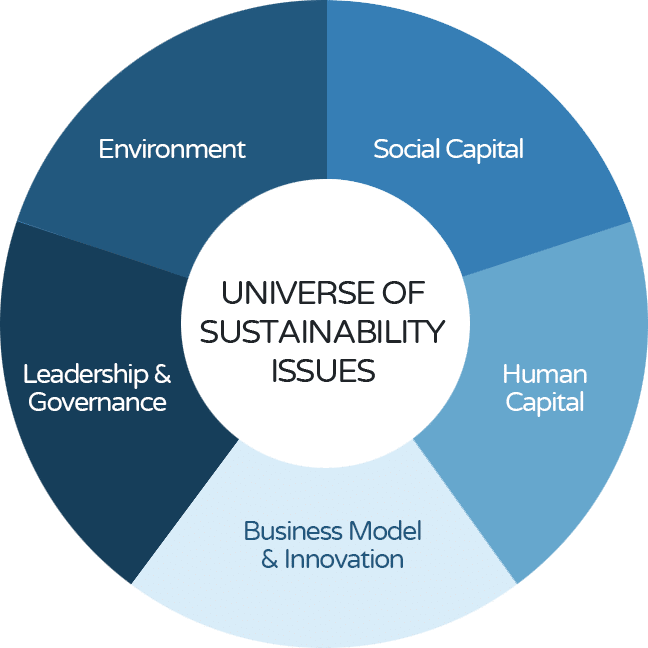

Environment

• GHG Emissions

• Air Quality

• Energy Management

• Water & Wastewater Management

• Ecological Impacts

Leadership & Governance

• Business Ethics

• Competitive Behavior

• Management of the Legal& Regulatory Environment

• Critical Incident Risk Management

• Systemic Risk Management

Business Model & Innovation

• Product Design & Lifecycle Management

• Business Model Resilience

• Supply Chain Management

• Materials Sourcing & Efficiency

• Physical Impacts of Climate Change

Social Capital

• Human Rights & Community Relations

• Customer Privacy

• Data Security

• Access & Affordability

• Customer Welfare

• Selling Practices & Product Labeling

Human Capital

• Labor Practices

• Employee Health & Safety

• Employee Engagement, Diversity & Inclusion

Attracting a Range of Investors

ESG reporting and investing certainly began with publicly traded companies providing data and being ranked on various ESG Indexes, such as the MSCI Indexes. However, the expansion of impact investing by private equity and venture capital means that companies at all stages of development could benefit from ESG reporting. Some high-flying examples of ESG-minded VC funds include Obvious Ventures that funded Beyond Meat in its early days back in 2014 and Base10 Partners that is IT-oriented.

A big reason that VC funds are starting to take ESG seriously is the growing perception (and track-record) that ESG transparent companies outperform. Marija Kramer, who is the head of ESG at the ISS ratings agency, explained that companies are

“seeing the value in sustainability and putting their own programs in place internally, because they, too, think that it’s an important variable to their own viability in the long term.”

Another reason for a company to monitor and/or report ESG data is to be able to demonstrate progress to itself and others. Investors respond to operational improvements, particularly those that are quantified. The collection and analysis of these data over time can help a company diagnose and troubleshoot problems before they are financially damaging. In this way, internal ESG reporting can help de-risk operations, and all investor classes will welcome the commitment to de-risking.

Climate Change Disclosure and ESG

The elephant in the ESG room is Climate-related Financial Disclosure. And like an elephant in a watering hole, it has a tendency to muddy things up. Specifically, people tend to conflate the concepts of climate-related reporting with environmental reporting, while we in the bioeconomy know that environmental reporting is multi-faceted and so much more than climate reporting. As with other ESG reporting there are two sides to the coin: 1) reporting on your company’s impact on climate change, i.e. emissions, and 2) reporting on the impact of climate change on your company, i.e. risks and risk mitigations for your business.

Climate-related disclosure has a lot of momentum and some strong backers. The Task-Force on Climate Related Financial Disclosure (TCFD) is a well-funded and ambitious effort that is driving wide spread change among publicly traded companies. There is tremendous pressure on institutional investors to participate in the TCFD. As reported in the Financial Times,

the investor-led Climate Action 100+ campaign is driving big companies to set targets on reducing emissions and reporting on their progress. For example, this year, Shell did an about face and agreed to set hard targets, whereas before it was less ambitious.

We believe that bioeconomy companies, many of which are focused on emissions reducing products across the spectrum of fuels, chemicals, and materials, are well positioned to benefit from investor appetite for climate-related investment opportunities. If a company is producing a product with a low CI score, then it should benefit from both policy and investor appetite. However, we don’t support the idea of climate-related reporting as somehow distinct. It is a cornerstone of good ESG reporting, but not the entire story.

Conclusion

News & Views

• Why Embracing Failure is Good for Business

• Ethics in ESG Investing: 9 Ways to Establish an Ethical Framework

• Understanding ESG Investing: Frameworks, Reporting, and Stakeholders

• Impact and ESG Investing Through the Financier’s Eyes

• The Importance of Measuring and Managing ESG to Attract Financing

• Taking Advantage of USDA Biorefinery Funding Opportunities

• 10 Things to Do While Waiting on the USDA 9003 Solicitation

Podcast Appearances

GBS Aims to Create a Low Carbon Bioeconomy

What People Say

My clients and I have worked with Cindy for several years in close association. Cindy is the absolute best government funding proposal drafter with whom I have worked. She has worked with us on approximately 12 comprehensive proposals for government funding and her fabulous work qualified each of these clients as a finalist for funding against scores of other proposals in a highly competitive setting. I recommend Cindy highly.

Mark J. Riedy, Partner

Kilpatrick Townsend & Stockton LLP

Victoria Gunderson, Coordinator

Climate Task Force, Office of International Affairs U.S. Department of the Treasury

I’ve had the pleasure of serving with Cindy on the Renewable Energy & Energy Efficiency Advisory Committee to the Secretary of Commerce for the past 8 years, including her term as Committee Chair. As a leader of the Committee, Cindy inspired her colleagues and advanced the renewable energy transition agenda, drawing on her senior level experience in the biofuel sector and service on multiple industry boards and committees.

Ken Kramer, Founding Partner

Rushton Atlantic, LLC

Richard Altman, Executive Director Emeritus

Commercial Aviation Alternative Fuels Initiative

Duane Adelson, CEO & Managing Director

Modern Capital Strategies, Inc.

Jim Lane, Editor and Publisher

The Daily Biofuels Digest and the Weekly Circular

Debra Nesbit, USDA Coordinator

Live Oak Bank